Madame Walker Didn’t Live Here: Harlem Architecture After the Renaissance

Ivey Delph Apartments, 1951

Architect: Vertner W. Tandy

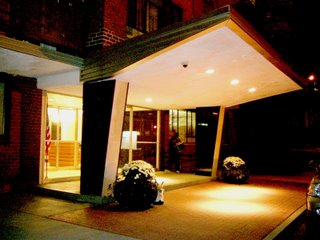

Lenox Terrace, 1957

Architect: S. J. Kessler & Sons

The architecture of modern Harlem, post-renaissance, from the late 1930’s through the post-war years has been defined as much by what it eradicated as by what it produced. The architecture of the Moderne, International Style and Post-Modernism for many Harlemites represents intervention by government and urban renewal more then any kindred or homegrown inspiration. An exception to this could be made for Harlem clubs of the late 30’s through the 1950’s. Surveying images of Small’s Paradise, “newly renovated and air-conditioned,” Sugar Ray’s or the sole surviving Lenox Lounge reveals Harlem club owners were supportive patrons of the modern, commissioning distinctive contemporary spaces to the apparent delight of their clientele. In looking for a similar architectural exuberance in residential and institutional architecture I went searching about Harlem for examples to recommend.

A rewarding find was the Ivey Delph Apartments, 1951 at 19 Hamilton Terrace. This modest, yet elegant Moderne styled apartment building is unique for its restraint and compatibility of scale with neighboring brownstones. Designed in 1948 by Vertner Tandy the first licensed African American architect in New York. Developed by Dr. Walter Ivey Delph, a prominent Harlem doctor and real estate investor who saw the apartments as an opportunity to provide a better and more healthy living environment for African Americans. The Ivey Delph Apartments was the first large-scale housing project by and for African Americans in New York backed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage commitment. The six-story beige brick building retains its historic architectural details, including a series of curved projecting balconies that rise above the building’s recessed entrance.

For international-style high-rise apartment living my sentimental favorite is Lenox Terrace, 1957 by S. J. Kessler & Sons located on 135th Street between Lenox and Fifth Avenues. Long before television’s George and Louise Jefferson gave definition to an urban African American version of “moving on up,” high-rise style, most Americans were glimpsing fantasies of it in movies of the 1950’s and early 60’s. Urbane “advertising executives” like Rock Hudson and Doris Day had sleek, modern “pads,” complete with balconies, automobile drop off and doormen at the ready. For the middle-class Harlem resident desiring a similar high-rise setting, Lenox Terrace was it! One can still feel a rush of 60’s Ebony glamour as you’re whisked off 135th Street and on to the cloistered circular driveway that deposits you under a cantilevered entrance of polished granite that connects to the building’s lobby.

Morningside Gardens, 1959

Architect: Harrison & Abramovitz

Schomburg Plaza, 1975

Architect: Gruzen & Partners

Other residential complexes noteworthy for their high-rise architecture and unique sighting are Morningside Gardens, 1959 by Harrison & Abramovitz set off the city’s street grid and within the rocky outcrops of Morningside Heights, and Schomburg Plaza, 1975 by Gruzen & Partners whose twin towers are positioned like giant octagonal pillars at Harlem’s gateway, the juncture of Fifth Avenue and Central Park North (110th Street) on Duke Ellington Circle.

Dance Theatre of Harlem, 1971 & 1994

Architect: Hugh Hardy

Malcolm Shabazz Mosque, 1965

Architect: Sabbath Brown

For post-modernists I have two out and out favorites. Dance Theatre of Harlem, 1971 & 1994 by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates at 466 W. 152nd Street. Originally a garage, the building through a series of renovations and additions culminating with the Everett Center offers a street front exuberance rivaled only by the company’s talented dancers. Banded in alternating rows of black and white glazed block, the building’s exterior mimics an un-built 1928 house design by architect Adolf Loos for another famed African American dancer, Josephine Baker. By contrast other corresponding walls are composed of a multi-toned pattern that replicates African, Kuba cloth. At the corner, in leaping profile, is an image of the company’s director, Arthur Mitchell, riding the pinnacle like a dancing weathervane. Though, currently lacking the “weathervane” like, crescent and star that crowned its peak, the Malcolm Shabazz Mosque, 1965 by Sabbath Brown located at Lenox Avenue and 116th Street is no less exuberant. Working with basic commercial materials and traditional Islamic forms, Brown’s conversion of the former Lenox Casino is in ways both simple and radical. The brash façade captures in a complex and contradictory manner the mosque’s kindred desire to promote a physical and spiritual presence in Harlem that would rival neighboring Christian edifices for the souls of Black folks following the death of Malcolm X. - The Harlem Eye / Harlem One Stop

Article First Published in The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine

Fall/Winter 2005-06

Text and Photographs by John T. Reddick

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home